'I wanted to show people,' he says, 'what it was like to be somebody who had a life that was contained in the Midwest, and who went on this journey, this adventure, and what his life became as a result. The film dramatises, in this sense, Weber's own journey from his provincial childhood in the mining and farming town of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, to his coming of age in fashionable New York. I hope that somebody in a small town somewhere might be inspired by it to go their own way.' 'It's a film about how things don't have to go in their normal progression. He himself sees it as a kind of escape movie: 'I just hoped this film might be interesting for students or anyone who ever picked up a camera in their life,' he says. He made it partly as a response to the deaths of several of the people he was closest to, including his sister, who died of cancer last year, and one of his oldest friends, Donald Sterzin, who had a room in Weber's beach house in Florida, and who died of Aids. It is billed as the very private filmmaker's most revealing self-portrait - its strands are linked by his plaintive voiceover - but the clues it offers to Weber's life open as many questions as they answer.

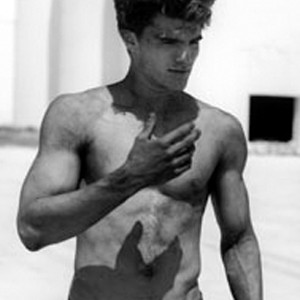

The project, like much of Weber's work, in outline sounds somewhat perverse, but the result is intelligent, stylish and even moving. Weber discovered Johnson, typically, aged 17, on the college wrestling team at Iowa University and talked him into coming to Hawaii to try on (and take off) lots of different clothes and be photographed obsessively by Weber and a 'camera club' of friends. We are here to talk about Weber's film, Chop Suey, a curious, beautifully constructed exploration of some of the photographer's longstanding obsessions: the life of the lesbian show singer Frances Faye the sun-baked memories of the 92-year-old English explorer Sir Wilfred Thesiger and, centrally, the personal transformation of Weber's latest model and muse, Peter Johnson. 'Many people,' he says, 'when they meet me, observe that I don't look much like my pictures.' He giggles. He tucks into a breakfast omelette and talks through his straggly grey beard in the most languid of voices, leisured and self-absorbed, like his photographs he has a blue handkerchief knotted around his head, a baggy shirt and trousers over a generous bulk (less six pack than Party Seven).

I meet Weber in a Brazilian café around the corner from the loft in Tribeca, near New York's Greenwich Village, where he has his studio. The images of this fantasy were, in large part, the vision of one man, Bruce Weber, who, in his extraordinary photo shoots for the underwear and perfumes of Calvin Klein and his 20-page portfolios of gilded American youth for Ralph Lauren, did much to transform the idea of male sexuality for our times (and sold a vast number of branded boxer shorts and pastel polo shirts into the bargain). The icons of that narcissism, the most visible signs of the idealised, toned, high-cheekboned life that wealth might buy just for you, were found on the giant billboards of the financial districts and in Times Square, and on the pages of men's fashion magazines that had been launched to cater to the dreams of potency among the new, youthful, share-optioned class. The fin de siècle American empire of money, born in the Wall Street dealing rooms in the late Eighties, sustained by the dotcom bubble of the Nineties, and just now beginning to unravel, borrowed myths of narcissism.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)